This is the second year I have participated in the ANZAC Day Blog Challenge. It is a privilege to share the stories of my family members who went to war. The stories of the men and women who served their country in each of the wars should never be forgotten.

Reading the World War 1 service records of my 1st cousins 3x removed, brothers, John, James and Albert McClintock one thing was obvious. The great adventure of war soon became a nightmare for the McClintock family of Grassdale near Digby.

Head of the family, John McClintock was born in Ireland in 1842. He arrived in Victoria in 1865 aboard the Vanguard. Somehow he ended up in the Digby area and in 1878 he married Sarah Ann Diwell, my ggg aunt and daughter of William Diwell and Margaret Turner. The following year, daughter Margaret Ann was born and in 1880, son David was born. Life seemed good for the McClintock family.

In 1882, the first tragedy befell them. Sarah passed away at just thirty-one. John was left with two children aged just three and four. Help was close at hand. In 1883, John married Sarah’s younger sister, Margaret Ann Diwell. At twenty-six and fifteen years John’s junior, Margaret went from aunt to mother to Margaret and David. In 1885, the first of eleven children were born to John and Margaret McClintock. A son, William Diwell McClintock died as an infant in 1887 but by 1902, when the last child Flora was born, Margaret and John had a family of six girls and six boys.

In 1913, a seemingly harmless activity of chasing a fox ended in another tragedy for the McClintocks. Eighteen-year-old Robert died from heart strain and tetanus as a result of his fox chasing.

Next was the outbreak of war in 1914 which paved the way for the greatest tragedy faced by the family. Three of the five McClintock boys, John, James and Albert, enlisted. Of the remaining two boys, David was too old and Thomas was too young.

JAMES RICHARD McCLINTOCK

James was the first of the McClintock boys to enlist. In Melbourne on 7 October 1915, the twenty-four-year-old signed his attestation papers and effectively signed his life away.

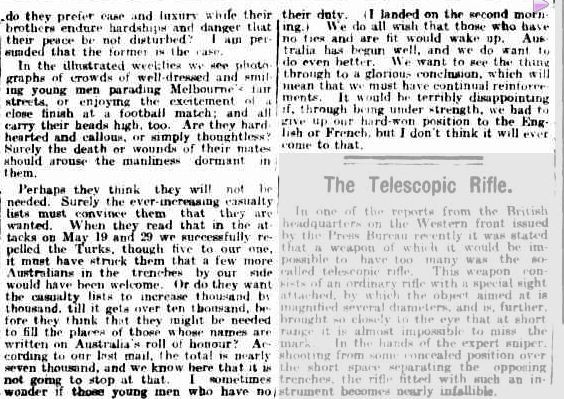

At the time, those of eligible age were bombarded with propaganda designed to drive recruitment. The horrors of war had already been felt at home with the Gallipoli landing earlier in the year. The recruitment campaign went to a new level. War was no longer the big adventure it was made out to be. Rather men were urged to fight in honour of their fallen countrymen who had died for them. Recruitment posters were everywhere and articles such as this from The Argus of 16 September 1915, must have gone a long way to persuading James to enlist the following month.

A CALL TO THE FRONT. (1915, September 16). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1956), p. 5. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1560597

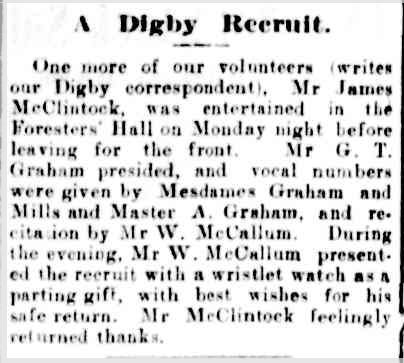

On 27 January 1916, James was given a send-off by the Digby community.

A Digby Recruit. (1916, January 27). The Casterton News and the Merino and Sandford Record (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), p. 3 Edition: Bi-Weekly. Retrieved April 19, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article74484539

24th Battalion 10 Reinforcements. Australian War Memorial http://cas.awm.gov.au/item/DAX1243

James sailed on 7 March 1916 aboard the HMAT Wiltshire with the 24th Battalion 10th Reinforcement. He arrived in England on 26 July 1916, and later France at Sausage Valley south of Pozieres on 5 August 1916. The 24th Battalion had been in France since March after arriving from Egypt. Previous to that the battalion had been at the Gallipoli landing in 1915.

On the day of his arrival, the 24th had seen action with casualties. They moved on from their position, making their way around the Somme before reaching Mouquet Farm on 23 August. The battalion settled in, digging trenches while they could. The noise of shelling was all around them.

THE FIGHT AT MOQUET FARM. (1916, August 31). Townsville Daily Bulletin (Qld. : 1885 – 1954), p. 4. Retrieved April 21, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58914119

The following day, the battle intensified. The 24th Battalion received an estimated fifty casualties. James McClintock was one of those

CASUALTIES IN FRANCE. (1916, October 3). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1956), p. 7. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1626549

Details surrounding his death were sketchy, so much so, his father employed the services of Hamilton solicitors, Westacott and Lord. On his behalf, they requested details of the death from the defence department to finalise necessary paperwork. As of November 1916, the final report on James’ death had not been received. It was clear his remains had not been found. He now lies below the former battlefields of the Somme with no known grave.

James is remembered at the Villers-Brettoneaux Military Cemetery. The cemetery has the remains of soldiers brought from various burial grounds and battlefields when it was created after Armistice. It also has memorials for those missing and with no known grave. James is one of 10,885 listed with such a fate.

Anxiety at home must have increased after news of the death of James. It was too late to talk John and Albert out of going to war. They had already arrived in England preparing to also travel to the battlefields of the Somme. At least John and Margaret would have been comforted that twenty-six-year-old John would be there to look after his younger brother.

ALBERT EDWARD McCLINTOCK & JOHN McCLINTOCK

John and Albert McClintock shared their World War 1 journey. They would have been spurred on by the enlistment of James and maybe envy that he was setting sail on 7 March 1916. The recruitment drive was in full swing and what man would not have felt that he was less of a man if he did not enlist?

No title. (1916, March 1). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1956), p. 7. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article2092485

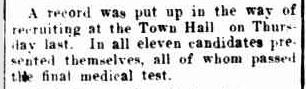

Albert enlisted six days before his brother John. At nineteen, he filled in his enlistment papers at Hamilton on 25 February 1916.

STREET APPEAL AT HAMILTON. (1916, February 26). The Ballarat Courier (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), p. 4 Edition: DAILY. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article74502118

On 2 March, John enlisted at Ararat.

The Ararat Advertiser. (1916, March 4). The Ararat Advertiser (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), p. 2. Retrieved April 20, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article75028814

John was married and living at Wickliffe with his wife Selina Miller Ford. They had married a year earlier. At the time of John’s enlistment, it is unlikely that the couple knew they were expecting their first child, due in December. Maybe John knew by 4 July, when he and Albert boarded the HMAT Berrima and sailed for war with the 29th Battalion 7th Reinforcements.

John and Albert disembarked in England on 23 August 1916. During December, back home, John’s wife Selina gave birth to their son, John James, his second name a tribute to his fallen uncle.

After time in England, Albert and John arrived in Etaples, France on 4 February 1917. On 9 February, they marched out into the field. The 29th Battalion unit diary notes their location on February 9 as Trones Wood near Guillemont and only ten kilometres from Mouquet Farm.

The battalion was not involved in any major battles at the time. It was at the Battle of Fromelles in 1916 and later in 1917 were a part of the Battle of Polygon Wood, but John and Albert had arrived between campaigns. During February 1917, members of the battalion were laying cable in the area around Trones Wood.

What exactly happened, three days later on the 12th, is not clear, however, the outcome saw both McClintock boys fighting for their lives with gunshot wounds to their faces. John’s service record notes the injury was accidental. He also had shoulder injuries and a fractured left arm. Albert lost his right eye and had an injured left arm and a fractured right leg. They were relocated over the next twenty-four hours to the 1st New Zealand Stationary Hospital at Amiens.

On 17 February, John and Albert’s war-time “adventure” together would end. Albert was transferred from Amiens to the 13th General Hospital at Boulogne, leaving John fighting for his life at Amiens.

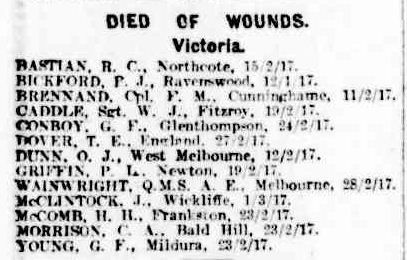

On 1 March 1917, John McClintock passed away from his wounds. He was buried at the St Pierre Cemetery at Amiens. Both boys said goodbye to France on the same day, as it was that day that Albert sailed for England. After only twenty days in the country, and no active fighting, one had lost his life and the other had suffered life changing wounds.

AUSTRALIAN CASUALTIES. (1917, March 16). The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1956), p. 10. Retrieved April 19, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1604104

On 28 February 1918, over twelve months after the incident, Albert was discharged from Harefield House Hospital, north of London, the No.1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital. He remained in England until May when he returned to Australia.

Digby. (1918, July 25). The Casterton News and the Merino and Sandford Record (Vic. : 1914 – 1918), p. 3 Edition: Bi-Weekly.. Retrieved April 19, 2012, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article74221588

So Albert was home and the war had ended. Life was expected to go on. On the outside that is what it did. There would have been some brave faces at the welcome at Digby.

Albert married Doris Hancock around 1920 and they raised a family of seven. He died in Digby in 1970 aged seventy-four.

John’s wife Selina never remarried and remained in Wickliffe most of her life, finally passing away in Adelaide in 1960. John jr enlisted in WW2 but was discharged early. For Selina, there was a constant reminder of John’s sacrifice on the Wickliffe War Memorial.

Parents John and Margaret McClintock did not live long past the war. The loss of one son would have been enough for any parents to bear, but two would be heart-wrenching. Another tragedy bestowed them with daughter Flora passing away in 1921 aged just nineteen. John passed away in 1923 aged eighty and Margaret in 1932 aged seventy-four.

On the inside, those people could never have been the same as they were before the war. In Albert’s case, the loss of an eye and memories of his short time as a soldier would have lived with him forever. For the others, the deep loss each suffered must have been immense.

This story interested me in a number of ways. In particular the timing and the locations of the McClintock brothers while in France. They were each there for such a short time and in similar towns and villages.

Maybe, in those last days before the departure of James, the brothers talked about meeting up somewhere, sometime during their war adventure. They were very close. James was killed only six months before John and Albert arrived in the same area of France he had fallen. They marched the same roads. Maybe at some time they did in some way pass each other by. As John and Albert marched to Trones Wood they could well have passed the final resting place of their brother James.

Today, John and James lay around forty kilometres away from each other in France. Albert is buried at Digby, thousands of kilometres away from his brothers, but I am sure he left a part of his heart in France the day in left in 1917.

LEST WE FORGET

REFERENCES:

Australians on the Western Front 1914-1918

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

What a sad story. Poor family. What is even more sad, is that it is not an untypical loss. “The War to end all Wars”. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

As a mother of 3 sons, I always find these stories incredibly moving. Lest we forget.

LikeLike

A wonderfully informative post Merron, but so sad. So many mothers died before their sons either came home, or they knew if they had been found or had died. I can’t imagine their pain.

LikeLike

hi Merron, I read your wonderful post the other day but only just getting back to comments. I was struck at the time how your McClintocks were in some of the same places as my James Paterson. Also your James and mine both on the wall at V-B. What terribly sad stories they are, the losses in peace as well as in war. How on earth did parents survive the grief? Poor Albert, injured so badly and having to live with that all his life and John’s wife Selina left behind. Put together another 46,000 stories of Australia’s “lost” men, like the ones we’ve all told this Anzac Day and the sheer pall of grief that lay over Australia/NZ must have been devastating.

LikeLike

Thank you to each of you for your comments.

I heard some stories yesterday, ANZAC day, about the physical and mental strain of parents who had lost sons at war. It made me think of John and Margaret. Not forgetting John experienced the loss of his first wife, two other sons and a daughter before he died in 1921.

Both of my posts for the ANZAC Day Blog Challenge have a war widow who never married again. In this post there was child also who never knew his father. Very sad.

Our stories are just a few of many many more all too similar.

LikeLike

Hello. I have just read this story while researching my husband’s family history and discovered a family connection to the McClintocks . Doris Catherine Hancock was my husband’s father’s sister. His name was Ellis Gerald Hancock. Its a pity that over the years many families lose touch with others in their extended families. I found it a very moving account of what its like for the soldiers and also for their families at home. A very sad time for all families .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Anne – Doris and Ellis are cousins of my grandfather whose WW1 service was driving fresh ammunition to the frontline of The Hindenberg Line and was Mentioned In Despatches. Doris planted his tree on the Digby Avenue Of Honour, and now she is buried at Digby cemetery with her husband Albert McLintock. Good luck in your research.

Thanks Merron for another excellent and detailed post.

LikeLiked by 1 person